In a pivotal scene in the new Netflix feature film “Rustin,” we see the protagonist, Bayard Rustin, in private conversation with Martin Luther King Jr. in the latter’s home. The scene makes clear why Colman Domingo has been nominated for an Academy Award for his portrayal of Rustin, even as the film has failed to garner other nominations.

Domingo’s performance makes the scene, and the film, burst with dramatic tension. His pitch-perfect, understated gravitas brings home the effect that director George C. Wolfe evokes with the dim lighting, the tight and shifting focus of the camera’s gaze on each man’s face, the softness of their voices, the tentativeness with which they speak to one another and the confessional character of the words they exchange. “This was not an easy journey for me,” Rustin says to King, who responds, “I missed you, friend.”

The scene powerfully conveys that Rustin was not only a friend and confidant of King, but very much his equal in stature and gravitas. Indeed, it was Rustin who introduced King to Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence, which would become central to his approach to social change. Despite this, most Americans are unfamiliar even with the name of this major figure, let alone his remarkable story.

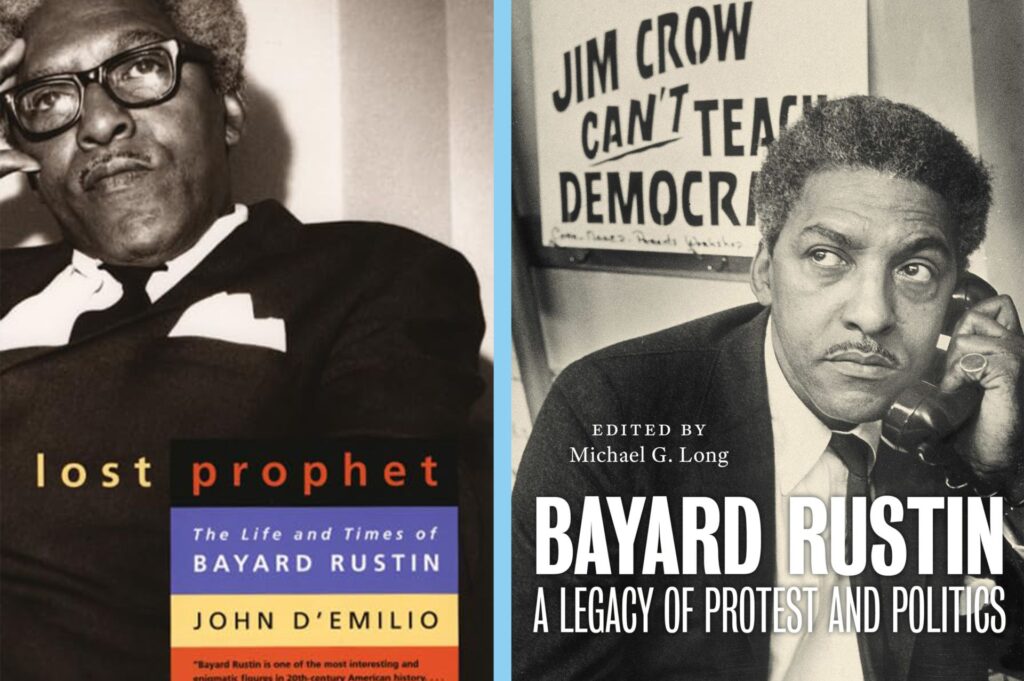

That might be changing, as Rustin is having something of a “moment.” In addition to the Netflix movie, the new book “Bayard Rustin: A Legacy of Protest and Politics,” edited by Michael G. Long, takes stock of the enduring significance of this complex, fascinating and controversial man. Why is this Rustin renaissance happening now?

Rustin is chiefly known for his role as the organizing mastermind behind the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (the “March on Washington,” as it was popularly known), at which King delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech. In what was, at the time, an unprecedented demonstration, over a quarter of a million people from all over the country descended on the American capital to demand civil rights for Black Americans. As the author Robert Kuttner has noted, “While we now think of peaceful protest marches on Washington as just part of the political choreography, until 1963 nobody had ever pulled one off.” That event, and King’s speech in particular, became an iconic moment in American history. Although Rustin had been an important voice and strategist in the peace movement as well as the civil rights movement, it was his role in the March on Washington that brought him to wide national attention, even landing him on the cover of LIFE, one of the most widely read magazines in America at the time.

It is therefore no surprise that Rustin’s role in that momentous event is the focal point of the action in “Rustin” or that it sucks up most of the oxygen in the room when commentators or historians mention his name at all. Yet there is much more to Rustin’s extraordinary life and work than that single accomplishment, as significant as it was. Rather than its pinnacle, we ought to understand the 1963 March on Washington as a pivot between the first and second halves of Rustin’s nearly half-century career as an activist. As the African-American scholar and Nation columnist Adolph Reed Jr. has noted, “Rustin’s politics and his role in the crucial debates over ways forward from the legislative victories of 1964 and ’65 don’t come up” in the film. Like Reed, I believe the biggest flaw in the film’s dramaturgy is the decision to close it with the March on Washington. The ending not only reinforces the tendency to see the march as Rustin’s crowning achievement; it also dissuades curiosity about what Rustin did in the following years, when he remained both active, including as director of the A. Philip Randolph Institute from 1965 until his death in 1987, and controversial.

The film’s choice of narrative arc dovetails with a common account of why Rustin was marginalized in the early 1960s, the period of its focus, why he came to be further marginalized later in his career and why he was nearly entirely forgotten for decades after his death. This common account, put baldly, is that Rustin was excluded from the movement and has been largely redacted from the history and memory of the movement because he was gay.

While it is undeniable that Rustin’s homosexuality was an important part of his biography and played a role in his marginalization, this common account of his status as a forgotten figure of the civil rights era is problematic. For one thing, it ignores the fact that Rustin himself rejected the view that his homosexuality was at the center of his activism. He attributed his center of gravity — his independence of thought and his universalism — to his Quaker upbringing rather than his Blackness or homosexuality. As James Kirchick, author of “Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington” (2022), wrote in The New York Times, this denial of identity politics “is a neglected part of his legacy worth celebrating, an intellectual fearlessness liberals need to rediscover.”

While Reed is right, in my view, to question the centering of the movie on the March on Washington, his review is excessively dismissive of the film, both in terms of its fidelity to history and its ability to bring its hero to the public’s attention. Reed accuses it of a series of errors in line with his suggestion that it is less interested in casting light on the intricacies of the civil rights movement than showing Rustin as one of the “Black American Greats.” Reed believes the film misses A. Philip Randolph’s role as the man who called for the march; “downplays the role of the labor movement in organizing the march, treating the unions offhandedly as obstructionist and instead attributing their initiative to smart, energetic young people”; and more broadly, like other Hollywood biopics, “perpetually fails to capture how movements are reproduced as mass projects, from the bottom up and top down, in a constantly improvised trajectory plotted in response to and in anticipation of layers of internal and external pressures.”

This seems to me unfair to “Rustin,” which stresses that it was through working with Randolph that Rustin pushed for King to join the march; makes clear that much of the practical and moral support for the march (including the buses) came from unions and — at least to a much greater extent than can be expected of a biopic that simply carries the family name of the film’s protagonist — stresses the anti-individualism of both Rustin’s political vision and his personal demeanor. We need to take on board Reed’s emphasis on what he calls Rustin’s “working-class-based, social-democratic politics,” but we also need to see what is partial in Reed’s own limiting picture of those politics, which were principally to do with nonviolence, internationalism and the (Judeo-Christian) prophetic tradition.

Any account of Rustin’s career, and his unique role as a theorist and practitioner of nonviolent resistance, must emphasize the international dimension of his work. Gandhi personally invited Rustin to voyage to India to participate in an international gathering of pacifists (that became the World Pacifist Congress) in early 1949. Although Gandhi was assassinated before the conference took place, Rustin’s visit to India and his in-depth conversations with Gandhi’s followers were formative experiences. This connection to Gandhi’s political philosophy, which many have argued Rustin articulated in a more coherent and consistent way than any other committed follower, was so deep and enduring that near the end of Rustin’s life, when a statue of Gandhi was dedicated in New York’s Union Square Park in October 1986, Rustin was tapped to be the keynote speaker.

The movie “Rustin” opens with a series of instantly recognizable images of the violence and vitriol with which white Americans reacted to Brown v. Board of Education — the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision that ruled racial segregation of children in public schools unconstitutional. We see the year 1960 appear on screen as we hear the important civil rights leader Ella Baker saying, “Things need to change and change now,” followed by notice of Rustin’s plan (in the end unrealized) to disrupt the Democratic Party’s national convention in Los Angeles that summer and call for urgent action on civil rights. This introduces the idea that between 1954 and the 1960 election of John F. Kennedy, King had come to see Rustin as an important advisor and strategist. Yet Rustin’s reputation as the leading American exponent of Gandhi’s beliefs and methods was established by the early 1950s, and it was this that led Baker and others to urge a young King to seek Rustin out, as we see dramatized in the movie’s opening scene.

The relationship between Rustin and King began amid the 1955-1956 bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. To protest segregated seating, African Americans refused to ride on city buses — an action triggered when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man and move to the back of the bus. From that encounter until King’s assassination 12 years later, Rustin was a central — and contentious — figure in the civil rights movement, always pushing the movement in general, and King in particular, to take stances that were as bold and transformative as possible.

But why was Rustin so controversial? Surely it had much to do with Rustin’s openness about being a gay man — a feature of his biography often stressed in recent accounts, such as John D’Emilio’s “Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin” (2004). Just as controversial, however, were some of Rustin’s core principles that cannot be reduced to his identity: his commitment to pacifism and nonviolence as a way of life and not just a means of protest, and his democratic socialism, with its focus on workers’ rights and economic justice as linchpins of the struggle for equality.

It is no accident that in the summer of 1963, King was organizing a “march for freedom” while Rustin, with his boss and mentor A. Philip Randolph (the founding president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters), was organizing a “march for jobs.” After much debate and internal strife, these planned demonstrations were eventually combined into the single March for Jobs and Freedom, which became a (if not the) signal event of the civil rights movement. But the struggle it took to get to that point, and for Rustin to be given the chance to speak from that platform, demonstrates the high degree of controversy he caused among more mainstream figures.

As dramatized quite accurately in “Rustin,” early in the planning of the march, NAACP President Roy Wilkins called Rustin and Randolph to communicate three main reasons why he was opposed to Rustin being its director, or even involved. Long quotes Wilkins in the introduction to his recent volume:

First of all, I know that you were a sincere conscientious objector during the war, but you have been called a draft dodger over and over again on the floor of the Senate and House. Second, you are a socialist, and many people think that socialism and communism are the same thing. Thirdly, you admit that you belonged to the Young Communist League.

Rustin’s homosexuality is not mentioned. It is true that Wilkins went on to say: “And then there’s the whole business of you having been arrested in California on a sex charge. Now, do you think we ought to bring all that into the March on Washington? Because it’s gonna come out, you know?” Wilkins was referring to the fact that Rustin was arrested while having sex with two men in a car in Pasadena while on a lecture tour in 1953, eventually pleading guilty to “lewd vagrancy” and serving 50 days in jail. Even here, though, it was not being a homosexual that Wilkins highlighted, but the arrest itself and criminal record, which he noted would surely become public.

One can argue that just because Wilkins delineated his reasons this way does not mean that the narrative that “Rustin was sidelined for being gay” is inaccurate, but it is at a minimum incomplete. The draft dodger charge in particular had been repeated a number of times on the Senate floor and in the context of the continuing (and not yet widely unpopular) commitment to universal conscription (or registration for conscription) we do Wilkins and history a disservice by turning his opposition to Rustin into homophobia.

Getting this clear also helps us disentangle the question of why Rustin was marginalized at that time from two related but different questions: Why was Rustin further marginalized in the last two decades of his life, after the assassination of King? And why is Rustin so unknown today — even after Obama gave him the Presidential Medal of Honor over a decade ago? There is no direct line from the controversy around Rustin in the late 1950s and early 1960s to his later obscurity. It was rather his commitment to nonviolence and a particular vision of social democracy, as well as his support for the Democratic Party and relative silence on Vietnam, that made him largely “untouchable” in the 1970s and 80s. And many of those features, but above all his committed opposition to identity politics, make it hard to “rehabilitate” let alone venerate him today.

Following repeated cycles of exclusion followed by restoration, Rustin continues to speak to us for a variety of reasons. He was an activist, first and foremost, but he was also a political thinker of real substance and importance, with ideas that continue to matter. In a series of essays and speeches written and delivered in the years between the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 1968, when Rustin was at the peak of his powers, he sketched out what I think we can consider the central tenets of his political philosophy, though it is not typically recognized as such. Rustin drew from an array of intellectual sources. His nonviolence, drawing on Quakerism and Gandhi’s ideas, was further nurtured by A.J. Muste, a minister and head of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a pacifist organization where Rustin spent several years as a field organizer. Rustin went through a communist phase in the late 1930s but broke with the creed in 1941, at which point Randolph, the towering labor leader, became his mentor. Rustin came to see nonviolence, internationalism, racial integration and economic justice in the form of labor-friendly industrial policy as mutually reinforcing. Indeed, he believed that none of these things could be actualized absent the others.

These views are worth revisiting at a moment when international and transnational institutions are at their least popular since World War II, when social movements across the ideological spectrum are deeply skeptical about the efficacy of nonviolent resistance, when the politics of identity and identification is celebrated by everyone from white nationalists and Christian nationalists to large portions of the political left, and when membership in labor unions remains at or near historic lows, even as labor battles have recently attracted attention and popular support.

The fundamental principle motivating Rustin’s thought and direct action was nonviolence, as he articulated it in the 1940s and 1950s. To quote from the statement Rustin drafted, which King and other mostly Black Christian leaders signed at the time of the Montgomery bus boycott, “Nonviolence is not a symbol of weakness or cowardice, but, as Jesus and Gandhi demonstrated, nonviolent resistance transforms weakness into strength and breeds courage in the face of danger.”

Rustin argued that only nonviolence can guard against a propensity for self-regard and self-interest that are incompatible with seeking justice for all and rejecting injustice against any. This is the deep fount of the oft-quoted entreaty to “be” the change that one wishes to see in the world. Although often attributed to Gandhi, what he actually said (in 1913) was: “If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him.”

Yet Rustin was also convinced that what he was advocating was nothing less than a revolution. Writing in 1965, Rustin stressed that it was hard for Americans — and even harder for Europeans — to understand the nature of the “civil rights revolution” because of a common assumption that revolution necessarily involves an attempt to seize political power (typically by force) and a commitment to constitutional change, and because:

Revolutions as we have known them invariably have used any form of power and in any degree — whatever it can get into its hands for the accomplishment of its aim, the achieving of power. By and large, the Negro revolt has denied that it is interested in, nor has it used, violence. It has limited itself in tactics and stratagems to nonviolence.

In the essay “From Protest to Politics,” which Rustin wrote immediately after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and some months before the 1965 uprising and violence in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, he noted that the passage of the Civil Rights Act was just the beginning of a revolution that would be required to achieve justice for Black Americans. Rustin linked his commitment to racial integration with the importance of just development in an industrial economy, seeing this as a natural development of the nationalization of the movement and the shift from desegregating the South to creating a more equal society nationwide. As Rustin put it:

It was also in this most industrialized of Southern cities [Birmingham] that the single-issue demands of the movement’s classical stage gave way to “the package deal.” No longer were Negroes satisfied with integrating lunch counters. They now sought advances in employment, housing, school integration, police protection, and so forth.

If achieving justice and equality for Black Americans requires nothing short of a revolution, why was it necessary that this revolution be nonviolent? Rustin addressed this question in texts written in the immediate aftermath of the assassination of King on April 4, 1968, and his argument for nonviolence at this time should be seen in its context. Rustin was continuing a debate with Malcolm X, whose ideas had, if anything, become better known and more influential in the three years since his assassination. A profound shift had occurred following the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. The main development was an increasing frustration with the principle of nonviolence among younger activists who had come of age in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), whose national chairman in 1966, Stokely Carmichael, coined the term “Black power” and led the organization — despite its name — in a decidedly more militant direction.

Speaking to the national media shortly after using the term on June 16, 1966 at a SNCC rally in Mississippi, Carmichael said, “When you talk about Black power you talk about bringing this country to its knees any time it messes with the black man. … Any white man in this country knows about power. He knows what white power is and he ought to know what Black power is.” Reading between the lines, we can see that for Carmichael Black power is precisely the program of economic and political separation, backed by the use of force if and when necessary, which was earlier advanced by Malcolm X.

Rustin rejected both the embrace of violence that Malcolm X popularized and for which Carmichael advocated and mobilized in the mid-1960s, and the Gospel-based embrace of loving one’s enemies that King and the SCLC had popularized in the 1950s, but which was failing to resonate with activists and young people by the late 1960s. Rustin insisted that even though white society “keeps providing the ghetto communities with evidence that unless they riot, they will get nothing,” all the same violence would “almost certainly come to reap only resistance and repression.” Rustin’s view of Black nationalism’s separatism and embrace of violence as misguided was in keeping with his own deeply intertwined beliefs in nonviolence and the connection of economic justice with racial justice. And both of these had roots in Rustin’s reading of the Old Testament. At this moment (1967/68), no less than over the prior 20 years of activism and writing, Rustin grounded his commitment to nonviolence in the Hebrew Bible’s ideal of loving one’s neighbor as thyself. The scholar Terrance Wiley sees Rustin’s skepticism about love as a principle orienting Black citizens toward the white majority as a rejection of the politics of love as such. If true, this would mean that, at this point in time at least, Rustin was to some extent siding with Malcolm X against King. I would argue, though, that Rustin’s insistence on the continuing practice of nonviolent activism, taken together with his advocacy for the Freedom Budget for All Americans proposed by A. Philip Randolph, tells a different story.

The Freedom Budget document was composed in 1966 and was an important conduit for the notion of “the 99%” as a basis for political mobilization, later so powerfully advocated by the Occupy movement and the Bernie Sanders campaigns of 2016 and 2020. The position paper called for a budget that would win the “full and final triumph of the civil rights movement, to be achieved by going beyond civil rights, linking the goal of racial justice with the goal of economic justice for all people in the United States” and would do so “by rallying massive segments of the 99% of the American people in a powerfully democratic and moral crusade.” The concrete proposals of this budget included a job guarantee for everyone ready and willing to work, a guaranteed income for those unable to work or those who should not be working and a living wage to lift the working poor out of poverty. These policies provided the cornerstones of King’s Poor People’s Campaign, conceived and carried out in consultation with Rustin and Randolph. The ambition of this program shows the alternative that Rustin was offering, to Carmichael’s Black power but also to the doctrine of loving one’s enemies and the building of coalitions solely around the goal of achieving political, rather than economic equality.

Rustin’s continuing connection to, and admiration for, Carmichael, and his concern regarding the latter’s ever-greater distance from the practice of nonviolent resistance is obliquely dramatized in one scene in “Rustin.” At a party, the character Blyden, a young Black radical, calls Rustin “irrelevant,” to which the protagonist replies, “It’s Friday night. I’ve been called worse.” In the film, Rustin wins over the Carmichael-esque Blyden and eventually recruits him to help train the unarmed “Guardians” deployed to ensure that the March on Washington is entirely nonviolent. In the real world, however, Rustin and Carmichael remained adversaries. Carmichael was still a student when he attended the Oct. 30, 1961 debate between Malcolm X and Rustin at Howard University, on the twinned questions of separation versus integration and violent versus nonviolent resistance, and claimed that was the night he became a nationalist. Five years later, writing in Commentary, Rustin bemoaned the split that “has already developed between advocates of ‘black power’ like Floyd McKissick of CORE and Stokely Carmichael of SNCC on the one hand, and Dr. Martin Luther King of SCLC, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, and Whitney Young of the Urban League on the other.” As we can see from Rustin’s framing of the issue in 1966, he was explicitly trying to find a “third way” between the philosophy behind Black Power and the Christian/Gandhian theology behind the SCLC.

While Jesus and Gandhi are the names one hears most when it comes to the philosophical and theological resources at the heart of the civil rights movement, Rustin is clear that his understanding of the principle of nonviolence is grounded in the Hebrew Bible. In a 1968 address to the Jewish activists of the Anti-Defamation League, Rustin shared that at times of confusion “I go back and read the Jewish prophets, mainly Isaiah and Jeremiah. Isaiah and Jeremiah have taught me to be against injustice wherever it is, and first of all in myself.” The doctrine he found there has two main principles: (1) The failure to create an equitable and just society is an offense against both God and one’s fellow human beings, and (2) this failure is best redressed through each individual’s recognition of the moral imperative to enact justice in oneself and one’s community. We often think of this as “the social gospel” in Christian theological contexts; as Rustin here emphasizes, it is an ancient Hebrew teaching.

Rustin suggested that by focusing on the Hebrew prophets one could advance the view that change is best sought through nonviolence without celebrating the putative “meekness” of Jesus’ teaching that had become not just unpopular but actively ridiculous to too many people. It is this teaching, Rustin provocatively suggests, that offers a path that can be shared by Black Muslims and Christians — it can mediate between Malcolm and Martin, so to speak. It rests at the heart of Rustin’s vision of the civil rights revolution and what he called “the work that needs to be done.” In Rustin’s modernization and reformulation of a program advocated by Jeremiah and Isaiah, we can see the recognition that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere and the complementary demand that all people of conscience commit to a “social and economic program” to create an equitable society. Crucially, this is not, or not merely, a moral principle; it is primarily a principle of action that brings about transformative change.

During the period after King’s assassination, Rustin was particularly concerned to argue that seeing civil rights legislation as the aim in itself was completely misguided. He railed against the inaction of the Black-Labor-Liberal coalition, which the March on Washington had mobilized, that followed the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. This coalition, composed chiefly of organized labor (led by the AFL-CIO, a confederation of U.S. labor unions), the institutional Democratic Party and young, grassroots activists, predominantly from urban and minority communities, was a precursor of what would be called the Obama Coalition. Rustin believed that the relative inaction of these parties during the second half of the Johnson Administration’s full term in office had led to a “process of polarization.” This polarization was taking place not only between liberals and conservatives, between the North and the South and between white people and other ethnic groups but also “within the Negro community.” He worried that “with the murder of Dr. King, it is likely to be accelerated.”

This proved to be the case with the “Southern strategy” of “remaking [the Republican Party] in the Southern white image,” in the words of Angie Maxwell, co-author of “The Long Southern Strategy: How Chasing White Voters in the South Changed American Politics” (2019). This was the signature of the 1968 presidential campaign of Richard Nixon. In the 1970s and 1980s, life in America’s cities grew increasingly bleak with “white flight,” economic disparities and the disinvestment of state and federal governments in urban areas. Telling in Rustin’s writing from this period is his prescient awareness that nonviolence, already very much doubted in the Black community, would only come to be more and more discredited. He wrote:

Dr. King’s assassination is only the latest example of our society’s determination to teach young Negroes that violence pays. [For] young militants will tell you, “this country was built on violence. Look at what we did to the Indians. Look at our television and movies. And look at Vietnam. If the cause of the Vietnamese is worth taking up guns for, why isn’t the cause of the black man right here in Harlem?”

Rustin’s reflection on King’s death and his call for the Negro-labor-liberal coalition to use the 1968 election to carry out President Johnson’s call to “build a ‘second America’ between now and the year 2000” are of a piece with his advocacy for the Freedom Budget that Randolph and Rustin had pushed Johnson to adopt, and which they hoped the union-supported campaign of Hubert Humphrey would write into its 1968 presidential platform. This, for Rustin, was the main work of this still-nascent civil rights revolution, which motivated him to support Humphrey’s nomination, further alienating him from youth activists who were first and foremost against the war in Vietnam and saw the nomination of Humphrey as a breaking point for their work in and with the Democratic Party.

This also points to a central factor in Rustin losing the confidence of many of his would-be fellow travelers in pacifist and socialist circles: Vietnam. Rustin lost a great deal of credibility with the younger generation of activists, and especially Black radicals, who saw Rustin as a sellout because of his insistence on not alienating the Johnson administration over the war. Rustin paraphrased those detractors in “Reflections on the Death of Martin Luther King, Jr.” published in the newsletter of the AFL-CIO, in May 1968: “How can you possibly defend, or be silent about, this white government sending Black men to kill other non-whites in Vietnam, and then tell Blacks here that we should practice nonviolence in our struggle?”

It is hard to avoid a deep sense of irony in Rustin being a pacifist and a conscientious objector during World War II (“the good war”) but then not wanting to rock the boat on Vietnam (a criminal war). It is not my aim here to defend or attack Rustin’s view on this — though I see legitimate issues of long-term strategy, political leverage and trade-offs involved, and he surely didn’t support the Vietnam war. At the same time, it must be stressed, he didn’t oppose the war publicly, as King eventually came to do. However one evaluates it, it is undeniable that, as the sociologist Sharon Erickson Nepstad discusses in her chapter in “Bayard Rustin: A Legacy of Protest and Politics,” Rustin’s refusal to espouse the anti-war position in the context of increasing polarization around the Vietnam War, especially after the shooting of student protesters by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State, was central to the “second wave” of marginalization of Rustin in the late 1960s and 1970s. And it has nothing to do with his being gay or anyone’s homophobia.

Rustin knew and understood better than anyone the contradictory dynamics of coalition-building in the United States. He understood from painful experience that fighting for justice will lead you into conflict with figures sympathetic to the call to end civil inequality who are unbothered by social and economic inequality. He knew that to stand up not just against violence but for nonviolence, that is not merely to oppose war but to advocate for social change through mass protest and coalitional politics, will lead you to be thought of as countercultural, unpredictable and unreliable, even within your own community. He thought cogently about how advocating both social revolution and nonviolence, while also representing in your person an alternative sexuality, will make you an outcast. The fruits of that life, and his examination of it, are still very much relevant for us today.

Despite the overall trajectory we see in “Rustin,” it is not so much his role as the organizer of the March on Washington, nor his exclusion — his excommunication, one could almost say — from the mainstream of the civil rights movement as an openly gay man that makes him a figure worth comprehending today. Rather, it’s the core of his robust and unique political philosophy in action — the coalitional politics that is aware of what we would now call intersectional identities but refuses to fetishize them — that makes him a man for this season.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.

"lasting" - Google News

February 29, 2024 at 06:02PM

https://ift.tt/vfRasUt

The Lasting Legacy of Bayard Rustin - New Lines Magazine

"lasting" - Google News

https://ift.tt/0qKHvyX

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Lasting Legacy of Bayard Rustin - New Lines Magazine"

Post a Comment