Steve McQueen’s new film anthology series, Small Axe, chronicles events from the history of London’s West Indian immigrant community, covering the time period from 1969 through 1982. By spotlighting various notable Black Britons from this era—radicals, cops, writers, students, and more—the films portray the myriad experiences of Black figures and communities within the U.K. as well as the systemic racism they faced at all levels of British society.

On Friday, Amazon will release the first of five installments, Mangrove, about nine Black activists accused by the British government in 1970 of inciting a riot at a protest against the Metropolitan Police. The case became historic as the first instance of the high-ranking Central Criminal Court—known familiarly as Old Bailey—acknowledging racism within Scotland Yard. The case also marked a major milestone in the fight for civil rights within Great Britain, as all nine defendants were cleared of the most punitive charges.

It’s a story that’s personal for McQueen, who, in bringing it back into public consciousness, stated that he wanted to tell it as closely to detail as possible: “My dad was friends with one of the Mangrove Nine. It was crucial to me that my co-writer Alastair Siddons and I put all our effort into research and to retelling this story with as much accuracy and care as possible.”

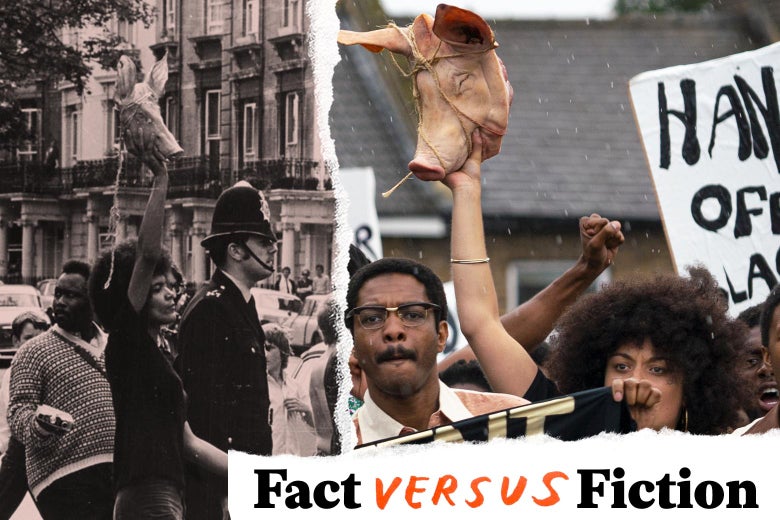

We checked his telling against accounts of the nine defendants, the lead-up to their trial, and their case itself, to answer questions like: Did one activist really carry a pig’s head while marching? Here’s what we found.

The Mangrove Restaurant

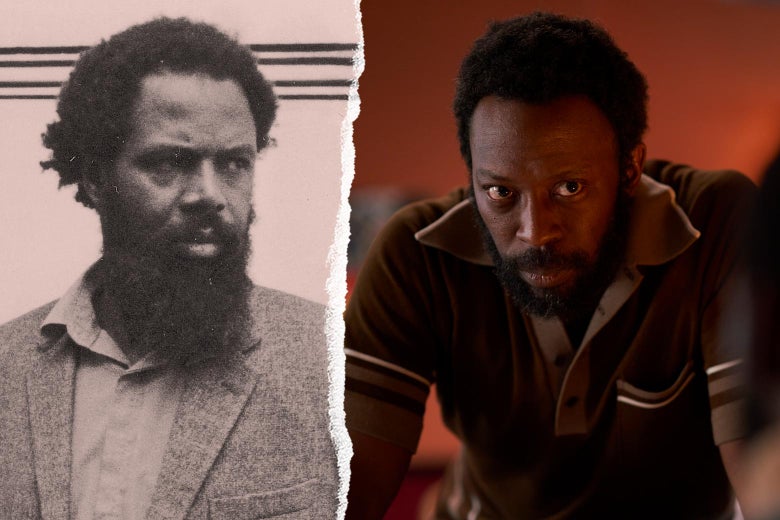

The Mangrove in Mangrove Nine refers to a restaurant of the same name that was opened in Notting Hill in 1968 by Frank Crichlow (Shaun Parkes), a Trinidad native who’d migrated to the U.K. after the war. As depicted in the episode, the Mangrove became a favored meeting spot for the local Black community, who enjoyed the West Indian cuisine, the live music and hospitality, and the opportunity to meet and converse with others in the neighborhood. It became a prominent-enough spot that musicians like Diana Ross and Jimi Hendrix also passed through the restaurant on their tours (though these visits are not depicted in the film) while activists, including members of domestic Black Panther chapters, likewise patronized the business. Mangrove portrays Crichlow as more of a reluctant activist than he reportedly was in real life—according to Blackpast, by the time he’d opened this restaurant, he’d been a committed Black Power activist.

I could not verify whether, as shown near the beginning of Mangrove, cops like the infamous Constable Frank Pulley (Sam Spruell) actually sat outside the restaurant in their cars, monitoring the establishment and disparaging the Black owners and diners—or whether the same cops used the results of card games played within their stations as pretenses to harass and detain Black residents. However, police raids of the Mangrove led by Pulley were indeed troublingly common, with the Metropolitan department often searching the establishment for drugs and sex workers, even though Crichlow himself did not approve of any illegal drug use and nothing outside the law was ever found on the premises. And, as chronicled by several outlets, Pulley in real life definitely had a reputation for aggressive, bigoted policing methods. At one point early in Mangrove, Pulley, while intimidating Crichlow, also mentions past “antics” at “the Rio,” referring to the El Rio café the real-life Crichlow had opened in 1959 and ran before he set up the Mangrove.

After multiple raids by the cops, the Mangrove’s alcohol license is revoked—in actuality, the Kensington and Chelsea Council had taken away the restaurant’s license to operate as an all-night café in December 1969, allowing it to only serve takeout food after a certain time.

Shortly after this, Crichlow decides to shut down the kitchen and fully turn the Mangrove into a 24/7 gaming unit. Clive Phillip, a friend of Crichlow’s, has said that the restaurant had “stopped cooking” after multiple incidents and that he and others in the community would “go in there and sit down and play penny poker and give Frank moral support.” The scene where Crichlow finally gives permission to local Black Panthers to hold meetings upstairs, while business as usual goes on in the ground floor, has it flipped: “You had the restaurant upstairs, but downstairs people were busy preparing placards,” Phillip told the BBC.

McQueen also uses other historical allusions of the time period to more subtly convey the racism embedded within British politics and life during that era: As Crichlow walks throughout London near the beginning of the movie, he strolls past graffiti of a British racial slur and letters reading “Powell for P.M,” referring to Enoch Powell, then a Conservative member of Parliament widely recognized for his anti-immigrant “Rivers of Blood” speech and his opposition to the anti-discrimination Race Relations Act 1968.

The Nine

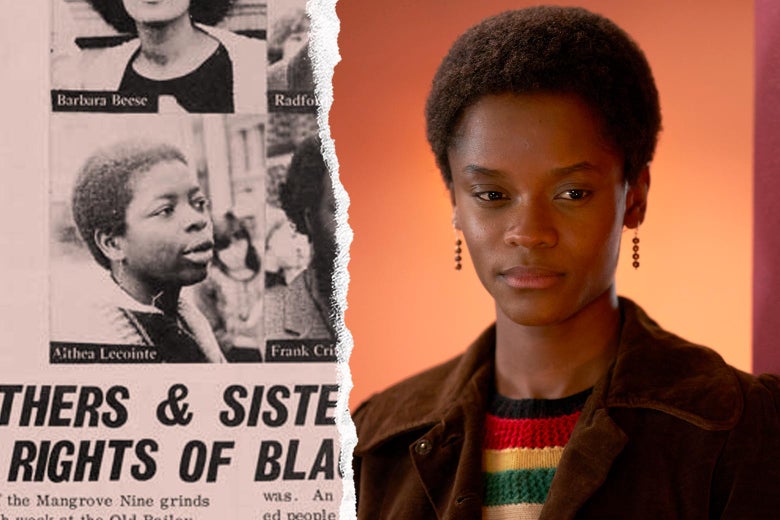

The full “Mangrove Nine” consisted of Crichlow, Barbara Beese, Altheia Jones, Darcus Howe, Rupert Boyce, Rhodan Gordon, Anthony Innis, Rothwell Kentish, and Godfrey Millett. The film primarily focuses on the first four figures, though all of them are depicted in some capacity, whether marching, planning legal strategies, or testifying from the stand. As shown on screen, Beese (Rochenda Sandall) and Howe (Malachi Kirby) were in a relationship at the time and had had a child together. Beese and Howe were also involved with the Panthers, as was Jones (Letitia Wright). Today, Beese and Jones are the only two surviving Mangrove Nine defendants.

The Protest

After the multiple raids on the Mangrove, Crichlow finally sanctions an effort for an anti–police brutality and Mangrove defense march in Kensington, taking the pleas of his Black Panther friends Darcus Howe and Altheia Jones to heart. About 150 people showed up on Aug. 9, 1970, for the protest, and, as depicted, Howe did stand on top of a car and motivate the crowd through screeds he yelled through a megaphone. And, as seen in archival photos of the march, Barbara Beese really did carry a pig’s head. Mangrove shows the marchers making their way toward a nearby police station while chanting “Hands off Mangrove” and “We’re gonna get rid of the pigs,” and then yelling at the police standing out front until more officers come out and start beating members of the crowd. On that date, more than 200 cops were dispatched to monitor, accompany, and eventually rough up the protesters, although the sheer scale of the force used could not be captured on film.

The Trial

The broad outlines of the cinematic depiction of the case against the Mangrove Nine match up with the reality: The nine activists were initially charged with inciting a riot—a serious violation of British law—but had the case thrown out by a magistrate, before they were charged again by the director of public prosecutions, rearrested, and ordered to show up at Old Bailey.

As Mangrove shows, Howe and Jones ended up representing themselves, with the rest taking the counsel of barristers David Croft (Richard Cordery) and Ian MacDonald (Jack Lowden), the latter a committed white anti-racist who had formerly lobbied Parliament to pass anti-discrimination legislation. The details about the jury selection are also true to life: The defendants and their counsel argued for an all-Black jury, citing the principle outlined in the Magna Carta of a “jury of one’s peers” and, when turned down by Judge Edward Clarke (Alex Jennings), used their objection powers to turn away 63 white jurors. The ultimate panel, as seen on screen, ended up with only two Black jurors.

The trial lasted 55 days over 11 weeks. During the proceedings, a cop was actually evicted from the courthouse for gesturing at another officer testifying on the stand, though I could not verify whether this was actually Pulley, as shown on screen.

The nine were all eventually acquitted of the most serious charges, although some defendants still carried lesser charges. And while the ruling was couched in a literal both-sides statement—“What this trial has shown is that there is clearly evidence of racial hatred on both sides”—the acknowledgment of police racism from such a powerful court was an important turning point in the British justice system, and it pissed the police off enough that they continually demanded the statement be retracted. As Crichlow himself put it, years later: “It was a turning point for black people. It put on trial the attitudes of the police, the Home Office, of everyone towards the black community. We took a stand and I am proud of what we achieved—we forced them to sit down and rethink harassment. It was decided there must be more law centers and more places to help people with their problems.”

It is true that, as informational cards at the end of the movie show, police continued to harass Crichlow and the Mangrove for years afterward. The restaurant ultimately closed in 1992.

Entertainment - Latest - Google News

November 21, 2020 at 01:25AM

https://ift.tt/393naAA

Mangrove accuracy: fact. vs. fiction in Steve McQueen's Small Axe movie about the Mangrove Nine trial. - Slate

Entertainment - Latest - Google News

https://ift.tt/2RiDqlG

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Mangrove accuracy: fact. vs. fiction in Steve McQueen's Small Axe movie about the Mangrove Nine trial. - Slate"

Post a Comment