On September 4, 1957, Herman Counts, a professor of theology at North Carolina’s Johnson C. Smith University, planned to drop off his daughter in the circle in front of Harding High School, which she was attending for the first time. Located off of West Fifth Street at the edge of downtown Charlotte, Harding was built in 1935 and stood as an important part of the city’s landscape. It had been segregated since its founding, but in 1957 Harding finally faced the difficult challenge laid down by the 1955 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Like most schools in the South, Harding resisted desegregation, and its students were prepared to resist the arrival of its first black student, Dorothy “Dot” Counts.

In anticipation of unrest, Charlotte police barricaded the main road to the school, so Dot had to get out and walk. Herman’s friend Edwin Thompkins rode in the car with them and offered to join Dot while her dad parked. Herman looked at his daughter as she opened the door and reminded her of what he always told his family: “Hold your head high.” He knew what she would face on the way into the building. Daily threats had set the stage for what was about to happen.

With Thompkins walking slightly behind her, Dorothy Counts, wearing a new red and yellow dress made by her grandmother, with a long bow that flowed beyond her waist, waded into a sea of white rage. She was only fifteen years old, one of four black students chosen to integrate the schools in Charlotte. The other three didn’t face much resistance, because the White Citizens’ Council had chosen Harding as the place to make their stand. And stand they did. Dot Counts confronted a wave of hatred that morning, and it was captured by the camera of Don Sturkey, a photographer for The Charlotte Observer. As she walked toward the school, white students, their faces contorted with hatred and unmistakable glee, screamed, “Nigger go back home” and “Go back to Africa, burrhead!” They threw sticks and chunks of ice. They spat on her new dress. The police refused to protect her, staying at the other end of the street and watching the spectacle from a distance. No school officials or teachers were present to calm the crowd or escort Dorothy to class. Instead, with her head held high on her lanky five-foot-ten-and-a-half-inch frame, her brow furled with an intense stare that perhaps hid her fear, and her mouth twisted in a manner that revealed her horror and utter disgust, Dot walked a racist gauntlet to enter Harding High School.

She made the walk for just three more days before deciding never to return.

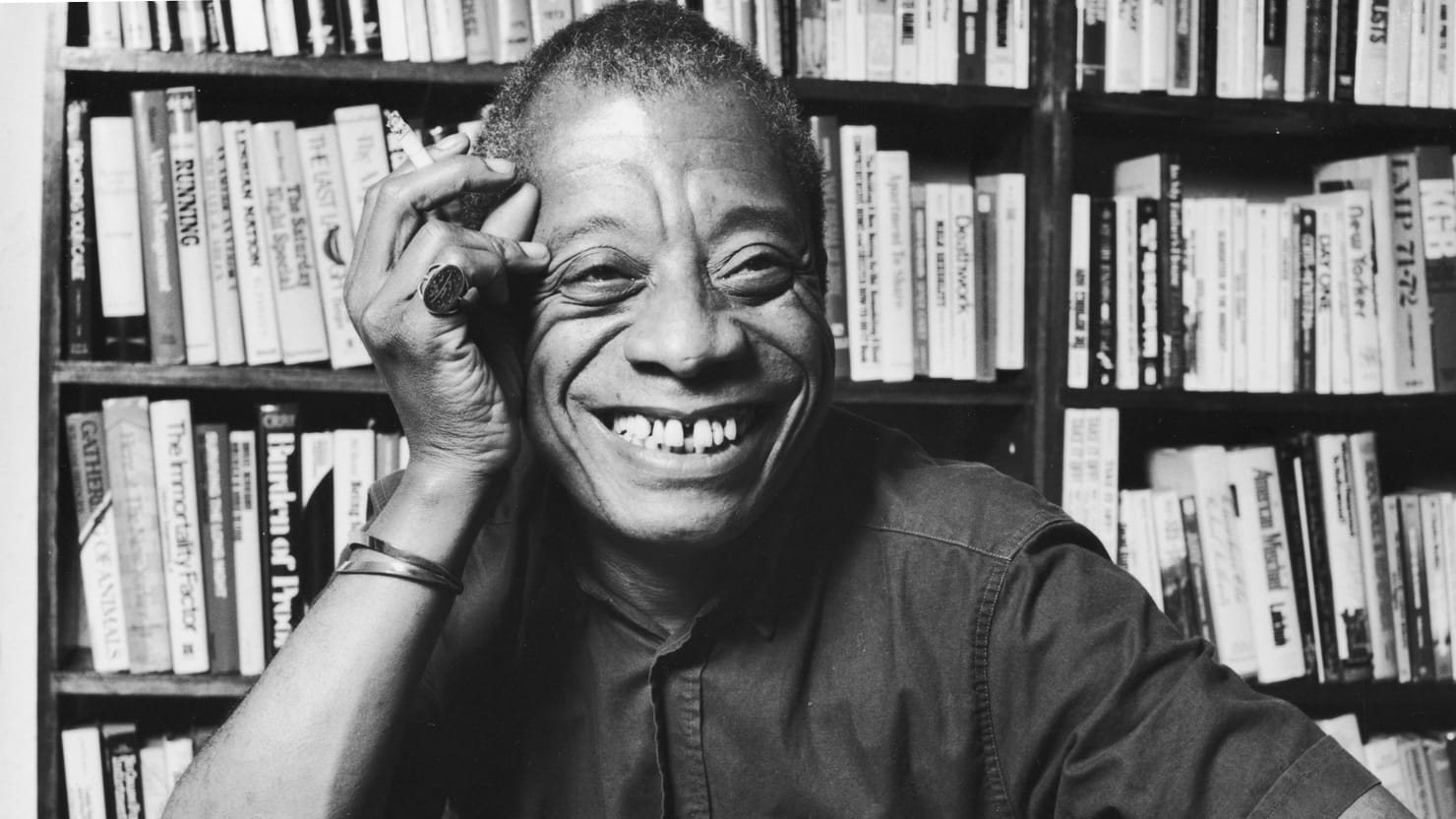

Don Sturkey’s photos of Dot’s harrowing experience soon traveled around the world, to great effect. In No Name in the Street, James Baldwin claimed that seeing newsstand images of Dorothy Counts while at the Sorbonne in Paris during the first International Conference of Black Writers and Artists led him to return to the United States after years of being away from home. He was covering the conference for the literary magazines Preuves and Encounter, and he recalled the photos confronting him as he walked from the meeting hall:

Facing us, on every newspaper kiosk on that wide, tree-shaded boulevard, were photographs of fifteen-year-old Dorothy Counts being reviled and spat upon by the mob as she was making her way to school in Charlotte, North Carolina. There was unutterable pride, tension, and anguish in that girl’s face… It made me furious, it filled me with both hatred and pity, and it made me ashamed. Some one of us should have been there with her! I dawdled in Europe for nearly yet another year, held by my private life and my attempt to finish a novel, but it was on that bright afternoon that I knew I was leaving France. I could, simply, no longer sit around in Paris discussing the Algerian and the black American problem. Everybody else was paying their dues, and it was time I went home and paid mine.

It makes for a galvanizing moment, with Jimmy moved to leave Paris by the cruelty visited on a child. But this was not quite the case. It could not have been the image of Dorothy Counts that spurred Baldwin to give up France. The incident at Harding High School happened in the fall of 1957, a year after the 1956 conference in Paris. In fact, the article Jimmy wrote at the time for Encounter, later published in Nobody Knows My Name in 1961, doesn’t mention the Counts photograph at all. In that essay, his memories reach for a different kind of sensory experience: “As night was falling we poured into the Paris streets. Boys and girls, old men and women, bicycles, terraces, all were there, and the people were queueing up before the bakeries for bread.” No mention of a photograph. No momentous decision.

Baldwin’s reflections on the photo of Dorothy Counts in No Name in the Street came some sixteen years after the events in Charlotte, and his memory failed him. In a sense, this was not a remarkable failure; throughout the beginning of that book, Baldwin warns the reader not to trust his memories. “Much, much, much has been blotted out,” he writes, “coming back only lately in bewildering and untrustworthy flashes.”

But it would be wrong to read this caution as mere reference to the fading memory of an aging mind. Instead, it is a consequence of trauma, not merely Baldwin’s own, but the collective trauma experienced in the course of a decade and a half of the betrayal of the civil rights movement. Over the sixteen years since Dorothy Counts attempted to desegregate Harding High School, Baldwin had witnessed up close the horrors of American racism. So many black children, in the South and in the North, had been subject to what she had experienced. Others had endured campaigns of violence against black people and the beatings and murder of protestors. Who knows how many black people line the bottom of the Mississippi River simply because they wanted to exercise their right to vote. Black leaders had been assassinated. Terror and disappointment had become defining features of the intervening years. And, through it all, America was still stuck in the morass of the lie.

Baldwin’s mistake in recalling why he returned to the United States revealed how trauma colored his witness. Memories fragmented or were repressed. Painful moments were triggered by random encounters. Grief and loss often overwhelmed everything. In No Name, he tries to capture, at the level of form, the effect of this trauma: The book reads like the reflections of someone who has been traumatized, folding back on itself and twisting time as past and present collide and collapse into each other. Memories flood and recede. After recalling the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and how King’s death and funeral affected him, Baldwin wrote, “The mind is a strange and terrible vehicle... and my own mind, after I had left Atlanta, began to move backward in time, to places, people, and events I thought I had forgotten. Sorrow drove it there... and a certain kind of bewilderment.” Here, in the after times, witness and trauma were inextricably linked.

So much of Jimmy’s life was filled with traumatic experiences that left permanent scars. The difficulties of his childhood, the dangers of sexual predators, his experiences with white police in Harlem, and his own feeling of being trapped by it all weighed heavily on how he navigated the world. Those wounds shaped his artistic vision. The trauma guided his eyes (and his pen) to the pain that lurked in the shadows of human experience and the various ways we all try to avoid it.

In Paris, Baldwin sought the critical distance necessary to reimagine himself apart from the assumptions and stereotypes of race that saturated American life. He needed the space to see himself and the country differently. However, this wasn’t an abstract or academic exercise for him. His very life depended on it. Jimmy knew he could not survive accommodating to the way black people were forced to live in this country. Only madness or murder awaited him there.

So his return to the United States wasn’t simply a political choice, as he seems to suggest in No Name. He needed the family he loved so dearly but had left behind. He wanted the comfort of black American culture—the sounds of the language, the taste of the food, its joys and pains. He wanted to experience again the elements of black life that danced around in his imagination and made its way into his writing. He first returned to New York for a period of nine months in 1954, bringing his play Amen Corner and the essay that would become “Notes of a Native Son.” He felt out of place. His years in Paris had created what felt like an unbreachable distance between him and the life he had left behind when he first moved to France. Old friends felt like strangers. And, of course, they didn’t know him any longer; he had been gone for seven years. But he returned to Paris only to find that it was no longer the same either. “Until I came back to America, I didn’t realize how many props I’d knocked out from beneath me. And, among them, as it turned out, was the prop of Paris,” he said to Fern Eckman. “I was almost as lonely in Paris when I went back as I had been here.”

Baldwin’s return to France in the fall of 1955 was riddled with a mixture of excitement about his modest literary success in the States and deepening depression. An intense love affair had finally ended, and Baldwin could only see ahead of himself a life of “fantastically unreal alternatives to my pain,” where even if he achieved fame he would not have love. Alone and desperate, he took an overdose of sleeping pills only to call his friend Mary Painter to tell her what he had done. She rushed to his side with a friend and helped save his life. Even in despair, Baldwin realized as he looked back on that time that something profound had changed in him. “I guess I was making up my mind, in some interior, strange, private way, about what I would do with the rest of my life,” he said. “And I think I was suspecting—though I don’t think I could have put it that way then—that I couldn’t really hope to spend the rest of my life in France. The attempt would kill me.”

It was in late September of 1956, after his attempted suicide, that he found himself at the Sorbonne covering the International Conference of Black Writers and Artists. It would have been a year after that, if indeed he saw it at the time, when Baldwin noticed Don Sturkey’s photo of Dorothy Counts with her slightly twisted mouth, her unshakeable pride, on the covers of newspapers.

Her photo was not the reason he decided to leave Paris. But when Baldwin finally went to the South in 1957 at the suggestion of Partisan Review’s Philip Rahv, he found Dot’s story. He arrived in Charlotte in the fall, after she had withdrawn from Harding High School. A woman, he reported, told him of the mob and of the spit that dripped from the hem of Dorothy’s dress. Several white students, he was told, begged Dot to stay. “Harry Golden, editor of The Carolina Israelite, suggested that the “hoodlum element” might not have so shamed the town and the nation if several of the town’s leading businessmen had personally escorted Miss Counts to school.”

But even when Baldwin wrote about his trip south two years later, in a 1959 article for Partisan Review, he did not mention the particular image of Dorothy he later claimed made such an impression on him. He offered instead a description of the end of Dorothy’s ordeal, her decision to leave the school and the regrets and trauma that accompanied it. Years later, in No Name in the Street, he would start at the beginning, with the image of her amid the hatred on her first day, and use the famous photo of Dorothy to justify his own decision to join the fray. Trauma did not come at the end, rather, it framed the story: “It made me ashamed… Some one of us should have been there with her!”

“Narrating trauma fragments how we remember. We recall what we can and what we desperately need to keep ourselves together.”

Looking back, after the deaths of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr., the photo with all of its pathos, anguish, and pride represented for Baldwin in 1972 the demand to bear witness to what was happening in 1956 and to what had transpired since, which led to his recollection of it in No Name in the Street. Dot’s eyes captured the trauma of that journey. Baldwin sought to narrate what happened on the eve of a social movement that would attempt to transform the country, and to testify to that odd combination of trauma and grit, which he now knew so well, seen in a fifteen-year-old black girl’s courage that spurred him, so he believed, to leap into the fire.

Narrating trauma fragments how we remember. We recall what we can and what we desperately need to keep ourselves together. Wounds, historical and painfully present, threaten to rend the soul, and if that happens, nothing else matters. Telling the story of trauma in fits and starts isn’t history in any formal sense. It is the way traumatic memory works: recollections caught in “the pitched battle between remembering and forgetting.” Facts bungled on behalf of much-needed truths. We try to keep our heads above water and tell ourselves a story that keeps our legs and arms moving below the surface.

By 1972, Baldwin can be forgiven for forgetting some things. He was trying to hold himself—hold us—together, after all. Four years into Nixon and the reassertion of the lie in the name of the “silent majority,” the previous decade’s struggle for equality was already receding into history, having changed laws but done little to address the value gap. In No Name, Baldwin moved from the image of Dorothy Counts to the events of the civil rights movement and, in the shadow of the dead and broken, sought to tell a story about the past that would, at least, give us some sense of direction in an uncertain moment. His misremembering sought to orient us to the after times of the civil rights movement and to call attention to the trauma and terror that threatened everything. “What one does not remember,” he reminds the reader, “is the serpent in the garden of one’s dreams.”

Baldwin’s view of traumatic memory is pretty consistent. In “Many Thousands Gone,” written in 1951, he makes the point about the relationship between memory, trauma, and the past.

Wherever the Negro face appears a tension is created, the tension is a silence filled with things unutterable. It is a sentimental error, therefore to believe that the past is dead; it means nothing to say that it is all forgotten, that the Negro himself has forgotten it. It is not a question of memory. Oedipus did not remember the thongs that bound his feet; nevertheless, the marks they left testified to that doom toward which his feet were leading him. The man does not remember the hand that struck him, the darkness that frightened him as a child; nevertheless the hand and the darkness remain with him, indivisible from himself forever, part of the passion that drives him wherever he thinks to take flight.

Some thirty years later, in his last book, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, about the Atlanta child murders, Baldwin begins with a meditation on the difficulty of remembering the patterns of the past and separating that from what he imagines himself to be able to remember. “Terror cannot be remembered,” he writes. “One blots it out. The organism—the human being—blots it out. One invents or creates, a personality or a persona. Beneath this accumulation (rock of ages!) sleeps or hopes to sleep, that terror which the memory repudiates.”

“My memory stammers, but my soul is a witness.”

— James Baldwin

The cruel irony, of course, is that the terrors move us about. We dig trenches to redirect the memories and to get them to flow away from us. But, like the waters of the Mississippi River, the memories always return, flooding everything no matter how high we build the stilts.

Although he was writing about the murdered and missing children of Atlanta, Baldwin revealed the deep fears that shaped his own memories.

It has something to do with the fact that no one wishes to be plunged, head down, into the torrent of what he does not remember and does not wish to remember. It has something to do with the fact that we all came here as candidates for the slaughter of the innocents. It has something to do with the fact that all survivors, however they accommodate or fail to remember it, bear the inexorable guilt of the survivor.

He had survived the storm of the modern black freedom movement (the assassinations, the betrayals, the madness) and lived, no matter the burden of guilt, to tell the story—especially on behalf of those who could not. “My memory stammers,” he wrote. “But my soul is a witness.”

In the end, we cannot escape our beginnings: the scars on our backs and the white-knuckled grip of the lash that put them there remain in dim outline across generations and in the way we cautiously or not so cautiously move around each other. This legacy of trauma is an inheritance of sorts, an inheritance of sin that undergirds much of what we do in this country.

It has never been America’s way to confront the trauma directly, largely because the lie does not allow for it. At nearly every turn, the country minimizes the trauma, either by shifting blame for it onto fringe actors of the present (“These acts don’t represent who we are”), relative values of the times (“Everyone back then believed in slavery”), or, worst, back onto the traumatized (“They are responsible for themselves”). There has never been a mechanism, through something like a truth and reconciliation commission, for telling ourselves the truth about what we have done in a way that would broadly legitimate government policies to repair systemic discrimination across generations. Instead, we pine for national rituals of expiation that wash away our guilt without the need for an admission of guilt, celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. Day or pointing to the election of Barack Obama, and in the process doing further damage to the traumatized through a kind of historical gaslighting.

This is the sinister work of denying the crime Baldwin wrote about. We lie and cover up our sins and mute the traumas they cause. We dissociate the trauma from our national self-understanding and locate it, if at all, in the ungrateful cries of grievance and victimization among those who experienced the pain and loss. “The biggest bigots are the people that call other people bigots,” George Wallace declared in 1968. By this logic, we identify scapegoats to bear the burden of our sins. Undocumented workers and Muslims become the “niggers” to fortify our sense of whiteness. We find security and safety in fantasies of how we are always, no matter what we do and what carnage we leave behind, on the road to a more perfect union.

The lie works like a barrier and keeps the nastiness of our living from becoming a part of the American story, while those who truly know what happened remember differently. “What is most terrible is that American white men are not prepared to believe my version of the story, to believe that it happened,” Baldwin declared. “In order to avoid believing that, they have set up in themselves a fantastic system of evasions, denials, and justifications, [a system that] is about to destroy their grasp of reality, which is another way of saying their moral sense.” The marks of Oedipus’s thongs remain, and some, like a Greek chorus, can see exactly where all of this is leading us.

From the book BEGIN AGAIN: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own by Eddie S. Glaude Jr. Copyright © 2020 by Eddie S. Glaude Jr. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Eddie S. Glaude Jr. is the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor at Princeton University and author of Democracy in Black.

"lasting" - Google News

July 04, 2020 at 12:27PM

https://ift.tt/2C1xHhx

How James Baldwin's Faulty Memory Yielded Lasting Truth - The Daily Beast

"lasting" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2tpNDpA

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How James Baldwin's Faulty Memory Yielded Lasting Truth - The Daily Beast"

Post a Comment